[ad_1]

By AGGREY MUTAMBO

Thursday December 7, 2023

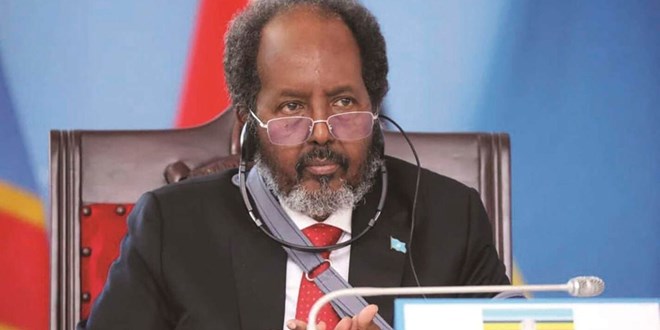

Somalia’s President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud. PHOTO | POOL

Somalia’s entry into the East African Community (EAC) as well as

promising domestic reforms helped earn the country a lifting of an arms

embargo imposed 31 years ago, initially to tame warlords but later

target Al Shabaab militants.

But celebrations for the move by the

UN Security Council (UNSC) last week could come with new worries among

peers in the EAC where irregular flow of weapons through porous borders

has often led to frequent violent extremism.

Lifting of the

embargo allows Mogadishu to arm its police and military forces with

modern weaponry. But peers in the EAC face Somalia’s big task of

ensuring weapons that fall in the wrong hands are not used perpetuate

violence in their borders.

Diplomats who spoke at the UNSC’s

briefing on Friday cited Somalia’s continued legal reforms in security

and financial sectors, as well as its readiness for integration with

neighbours among biggest influences to lift the restrictions.

Japanese

Diplomat Shino Mitsuko said her country supported the new resolution

because it targets violators rather than a government seeking to

rebuild.

She argued Somalia will now be free to engage in “enhance greater regional cooperation to degrade Al Shabaab in the region”.

Al

Shabaab remains banned from purchasing or accessing weapons in the

international market and countries must work together to ensure no

violations.

Abukar Dahir Osman, Somalia’s Permanent

Representative to the UN, said his country will now be ready to

“confront security threats, including those posed by Al Shabaab”.

“Sustainable

peace and security can only be achieved through a comprehensive

approach that integrates security measures with initiatives aimed at

fostering long-term stability and prosperity,” he said.

Somalia

announced it will immediately proceed with the second drawdown of

African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (Atmis) with a new batch of

3,000 troops expected to leave Somalia by end of this month. Atmis

should be completely out of Somalia by December 2024.

The move by

the UN Security Council meant President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud had

delivered two of his three promises; joining EAC and having an embargo

imposed in 1992 lifted. The third goal is to attain debt relief,

allowing Somalia to discuss lending terms with international financial

institutions.

All three are important but the arms embargo could

affect relations between Somalia and its federal states, as well as be

forced to make urgent reforms that could stop illegally re-arming Al

Shabaab from the national armoury.

In addition, critics say it

will not be Mogadishu’s headache alone. Hilaal Institute, a security

think-tank in Mogadishu, suggested the embargo which has lasted 31

years, was being lifted prematurely.

“The evidence suggests that

the premature lifting of the arms embargo could precipitate a range of

adverse outcomes, from intensifying clan conflicts and enabling illicit

arms flows to posing broader threats to regional and global stability,”

Hilaal concluded in advisory last week.

“The interplay of

domestic dynamics – the clan-based societal structure, limited

government control over ports of entry, open arms markets in Mogadishu,

and instances of Somali National Army (SNA) weapons appearing on the

open market.”

Just a week after Somalia had been formally

admitted into the EAC, the arms embargo lifting generated a celebration

in Mogadishu.

President Mohamud and his Prime Minister Hamza

Barre were saying the same thing: Somalia is ready to confront its

arch-enemy Al Shabaab now that it will be allowed to arm itself.

“The

voting in our (Somalia’s) favour has several benefits,” said the

president, noting that Somalia’s armed forces will be sufficiently

empowered.

“Next, this empowerment will pave the way for clearing

the Khawarij (religious deviants) from the country,” he added in clear

reference to the Al Qaeda-linked Al Shabaab.

Mohamud reiterated

that this total permission gives Somalia a leeway to buy the weapons it

needs to defeat terrorists and secure its borders.

“Besides,

members of the international community can have the faculty to offer us

arms and ammunitions that can help our drive to stabilise our nation,”

he said.

Perhaps Mogadishu’s first headache is to ensure it

remains united on the issue given the federated structure the country

has adopted in the last 15 years with regional governments enjoying

significant autonomy and laws leaving gaps for anyone to interpret.

Somaliland,

the breakaway region that self-declared independence more than 32 years

ago, on Saturday said the UN Security Council must tighten checks on

Somalia to ensure warlords do not emerge.

“We believe that

lifting the embargo at this time would have detrimental ramifications

for Somaliland, the Horn of Africa region, and the international

community,” Somaliland government said after the vote in a statement.

Somaliland

is yet to be accepted internationally as an independent country even

though it runs its own government, military, currency and central bank.

Its

history with the Somali civil war, that led to the initial imposition

of the embargo in 1992, is that the government of then Somali leader

Siad Barre bombarded its capital Hargeisa where a rebellion had first

emerged against Somalia.

Somaliland claims some 200,000 people

were killed in those episodes and says part of the problem was irregular

flow of weapons and no accountability on usage.

Recently, clan

militias engaged Somaliland in Las Anod, a region straddling Somaliland

and Puntland federal state. The clan militia have since pledged

allegiance to Mogadishu which they want to directly administer the

region until it creates sufficient structures to become a new federal

state.

But that is both a problem and benefit for Somalia. A

problem because the law does not yet guide on the formation of federal

states nor does it create a limit. But with the clans aligning with

Mogadishu, it means Somaliland loses more ground at seeking

international recognition.

“The emergence of clan militia groups

such as Lasanod ones, aligning themselves with extremist entities

presents a clear and present danger in the region. Lifting the embargo

could fuel these groups, jeopardising regional security and exacerbating

ongoing humanitarian crises,” Somaliland argued in a statement.

Both

Hargeisa and Mogadishu however agree that there are gaps in weapons

management, something which the UN Panel of Experts on Somalia had

argued in previous reports after it found weapons donated to the

government forces had been sold off in the black market to Al Shabaab.

Hargeisa

argues there has been no demonstration that Mogadishu can account for

its weapons and hence there is a danger of diverting weapons to terror

groups. The two sides also can’t agree on the definition of terrorists.

Yet, Mohamud did admit his government faces the challenge of establishing a proper weapons management system.

“It is the mandate of the government to keep strict records of arms inventory,” said Prime Minister Hamza Barre.

Usually,

Al Shabaab tends to increase its tempo of attacks both inside and

outside Somalia when it gains more access to weapons and money.

Previously,

the militant group smuggled charcoal to fund its terror attacks in

neighbouring Kenya and Uganda. Then the group changed its tactics by

infiltrating key government agencies like the revenue authorities and

security agencies. A top diplomat in Kenya said they have genuine

concerns about management of arms inventory, but said Kenya welcomed the

lifting of the embargo because it allows Somalia and peers to

collaborate better on security management as regional forces under the

Atmis start to leave Somalia this month.

In the past, Kenya had

been among countries that sought tougher sanctions on Al Shabaab

including having them listed in the same regime as Al Qaeda. But strong

lobbying from activists curtailed the move as some argued it could lead

to collective punishment of innocent civilians in areas Shabaab’s

control.

In Mogadishu, local radio shows aired call-ins from locals, with some being bland about the arms embargo.

“There

is no point in celebrating the lifting of the arms embargo unless the

authority establishes a demonstrable means of controlling the arms,”

quipped a listener of Kulmiye Radio, an independent broadcaster in

Mogadishu. Several other political figures in Somalia also took the same

cautious view.

But government officials see it as a first good

sign. The Resolution 2714/23 lifted Resolution 733/92, which had been

amended several times to reflect the menace of Al Shabaab.

The

council however will still require Somalia to submit a list of weapons

purchased to its sanctions committee, and Mogadishu is required to

establish a national inventory of weapons besides promoting adequate

training of the police and military.

The council also says

Somalia must also vet and license private security firms that seek to

import weapons into the country and that it must ensure those weapons

are not resold, transferred or supplied to entities that are not

entitled to use the equipment.

Ghanaian Diplomat Harold Adlai

Agyeman, speaking on behalf of Gabon and Mozambique (African members in

the council), said Somalia had already made positive steps in setting up

a weapons management system, “which has been recognised in the

resolution”.

[ad_2]